How might an amateur be able to observe an exoplanet?

To answer that question, we'll first ask: how might an exoplanet be observed? Let's not worry about technology just yet...assuming that we have the equipment, what techniques might allow us to "see" a distant world? And can amateurs do them?

The most obvious answer is to take a picture of one! After all, we're used to seeing things every day. Much of what we know exists is because we can lay our eyes on it. So, is it possible to take a picture of another world? Surely planets are too small and too distant and near stars that are too bright for us to take a picture of one. Direct imaging of an exoplanet isn't possible with even the best equipment available. Right?

Well...

|

| Three images of Beta Pictoris taken over 7 years time. |

In 2009 the ESO's VLT imaged Beta Pictoris. It did so in such a way so as to remove much of the star's glare. What was left revealed a bright spot. In 2009, a second image was taken. Then again in 2010. The resulting images reveal a planet in a near Saturn sized orbit.

OK, there's more data behind the pictures. These three images aren't enough to convince many that the bright spot is a planet. It could be another star with a high proper motion. And these images do nothing to show the object has or can change directions as one would expect an orbiting planet to do. But supplementary data exists to show that the bright spot is, indeed, a planet with roughly the mass of 7-11 Jupiters.

And it was caught on film! Well...caught on camera anyway.

And it's not the only system where exoplanets been imaged. Hubble has imaged Fomalhaut over several years to reveal a similar bright object projected to orbit its host star.

|

| A bright dust ring and embedded exoplanet imaged around Fomalhaut. |

Yeah, OK. Hubble the VLT, these are some serious telescopes! Certainly there's nothing a typical amateur can do to directly image an exoplanet...

...or is there?

|

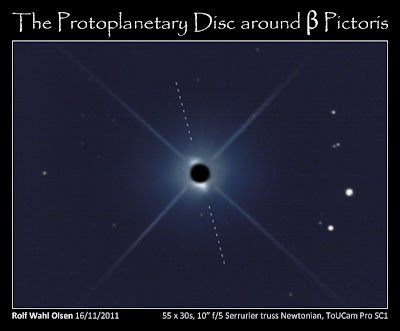

| Photo taken by Rolf Wahl Olsen showing the dust disk surrounding Beta Pictoris |

In 2011 Rolf Olsen took an image of Beta Pictoris. Well, many images actually...and some of Alpha Pictoris as well. When processed together, an image emerged that shows the dust disk surrounding Beta Pictoris.

How did he do this?

The basis technique is to image the target star...the one with the dust disk. Then image a comparison star. The trick is to image a comparison star under the exact same conditions as the target star. Color, magnitude, altitude, exposure time, etc...anything that may be different and effect the amount of captured light should be as identical to the target star as possible. Scientific papers on the Beta Pictoris system suggest using Alpha Pictoris for its proximity and similarity.

We now have two images...one of a star that we presume has "extra" light around it reflected from a planetary disk--or even a planet! And a second with a "normal" star without any extra sources of light around it. Subtract the two. In theory, the resulting image will only have the "extra" sources of light in it. i.e.: the reflection of the dust ring or...if extremely lucky...the reflection of light off an exoplanet!

In Rolf's image, the dashed line marks the known orientation of the dust disk. The bright "wings" off the star in the image align pretty darn well with the expected orientation! When you sit back and think about it, this is a phenomenal piece of work! Even f you don't want to spend the time to think about it, this is a phenomenal piece of work! Just trust me on that :)

Sure, not exactly an exoplanet image. And it may yet be a long time...maybe never...before we have the technology to truly image an exoplanet from our backyards. But this is impressively close!

Beta Pictoris doesn't spend a whole lot of time in my observable sky. But I wonder if this can be repeated with, say, Fomalhaut???

I'm itching to try!!!